All branding and marketing projects start with questions. Lots of questions. In order to uncover unknowns and proceed with confidence, we recommend starting with a Discovery phase. Learn all about Discovery for your next branding project in this free, 8-page illustrated guide.

From positioning statements to elevator pitches to taglines, here are eight messaging elements you can use to define and promote your business or nonprofit. (9-page PDF)

It’s a summer evening and you’re attending a benefit concert for a local nonprofit.

As your eyes sweep the crowd, you notice a 55-year-old woman subtly snapping pictures of the band that she’ll later post to Facebook or text to her kids. She has donated to the nonprofit for years, and the concert is just one more opportunity to make a contribution.

Meanwhile, a 37-year-old couple is hovering around the beer garden, waiting for their chance to take a picture with the nonprofit director and big benefactors so they can impress their Facebook friends. As they wait, they browse the organization’s website to learn about donation opportunities.

A group of 25-year-old friends first learned about the concert thanks to the trendy band. When they found out it was a benefit concert — extra bonus! As the lead singer croons, they artfully take pictures and videos for their Instagram feed: #giveback.

Everyone appears to be enjoying the evening, but as a member of the board of directors, you’re concerned that the nonprofit has missed an opportunity to drive home its message with potential advocates.

What could have been done differently?

Generational marketing, the strategy of segmenting audiences based on generational characteristics, provides marketers with insights to the preferences, ideals, and values held by different age groups.

This knowledge allows organizations to craft messages that will resonate with target audience segments. That said, as with any segmentation strategy, remember that each audience group is comprised of unique individuals. Be wary of making sweeping generalizations or stereotypical appeals.

Depending on your business sector, your unique selling point or brand promise could be cross-generational. This is especially likely if you’re directing a nonprofit.

Regardless, when sharing your message you’ll need to adjust your approach to effectively reach different generational segments.

Start with common characteristics, and then dig deeper for each targeted generation.

Once you’ve nailed down your message for each segment, you can ask:

So, how can you use generational targeting to drive engagement and action among different audience segments? Here are some ideas to get you started.

For Baby Boomers, your message could appeal to their desire for self-fulfillment by using the second person point of view. Also, do not remind them that they are aging.

When creating a compelling message for Generation X, focus on your brand value. Make a direct connection between their individual needs and how your brand could impact their life. Also, if appropriate, subtly appeal to status.

When targeting Generation Y (aka Millennials), brands have the opportunity to align their message with this generation’s desire to make a difference and help the greater good. If you do this while creatively communicating your brand’s personality, you’ve struck gold.

Another benefit concert has arrived.

This time, your nonprofit has a firm understanding of the generational differences and preferences among its target audience groups. With this knowledge, you’ve used targeted messaging in your pre-event promotions to encourage attendance.

You recognized Baby Boomers as valuable contributors, thanked them for their regular donations, and told them that the founders wanted to meet them in person at the concert. At the concert they received material about becoming a legacy donor, meeting their desire to make a long-term impact.

You encouraged Generation X to attend, since the funds raised could improve their families’ access to a new community initiative. The invitation to become a regular donor was included in their confirmation email.

You targeted Generation Y through messaging that clearly outlined how attendance would help the organization raise the remaining funds necessary to finish a community project. You also provided the opportunity to text your nonprofit a small donation, as the first step towards a long-term relationship.

As a result, attendance increased 20 percent over the previous year, and the nonprofit met its fundraising goal. Better yet, individuals from Generation X and Y — groups that had been minimally engaged — signed up for volunteer opportunities and sustaining, automated donations.

Knowing your target audience’s age and the factors that shape generational attitudes and perceptions allows you to craft a message that is more likely to resonate and drive action.

This article is also published on Medium.

Whether it’s a tagline or a slogan, a motto, or a mantra, the rules are the same. Effective communication starts with knowing who you are — what your mission and vision are, and where your strategic plan says you want to go. Differentiation is, after all, about being different. And touting your differences will, when done correctly, attract the right kinds of prospective students and donors while causing others to look elsewhere. And that’s the whole point. Institutions of higher education cannot be all things for all people, nor should they try to be.

It’s easy to be confused about the difference between slogans and taglines, so let’s sort this out up front. The two have similar, but distinct roles to play in marketing and differentiation.

A slogan is a catchphrase — a short string of words designed to catch people’s attention. It’s a hook. It’s something you can lead a marketing campaign with. Effective slogans are casual, memorable, repeatable in conversation, and sometimes they even get turned into musical jingles. Repetition, rhyme, or alliteration help make slogans memorable and easy to say.

Slogans can also be thought of as battle cries, often used skillfully by higher ed athletic departments to rally fans (and to sell tickets). Ideally, a slogan will cause people to feel something — hope, belonging, school pride, or whatever emotional quality you want associated with your brand.

A tagline, on the other hand, is something that’s tagged on at the end. Taglines are commonly placed after or below a logo or, say, at the bottom of a marketing brochure. Taglines are designed to be read (not said). You read the name of the organization first, then you read the tagline. Always in that order. Taglines are supposed to provide context or additional meaning to the brand name, and are particularly useful when introducing new entities into the world. Taglines can be derived from mission statements or brand promises, and, therefore, will live much longer than shorter-term campaign slogans.

While a good tagline might evoke an emotional response, it must first be functional: it should summarize your story, your purpose, or speak to the unique and specific benefits you offer.

Both slogans and taglines are messaging tools that can be used to differentiate an organization, but sometimes it’s hard to tell the difference between the two. Here’s a simple test: You know you’ve got a slogan if it’s able to work alone, with or without your logo. Otherwise, if the words are only meaningful when combined with your logo, you’ve got a tagline.

Not to purposely confuse things, but it’s worth pointing out that some taglines morph into slogans over time. This doesn’t happen often, but it’s possible for a tagline to become familiar enough that it starts to become useful on its own.

Because most colleges and universities have long, established histories and are well known either regionally or nationally, they usually don’t need — and probably shouldn’t have — a formal tagline attached to their logo. While slogans can be quite useful for specific marketing campaigns (capital fundraising, new student enrollment, etc.), taglines for higher ed institutions are typically pointless. Especially if the tagline does nothing to differentiate from the 4,000 other colleges and universities in the U.S.

Take “Your Future, Our Focus” for example. It’s the tagline of Northern Illinois University, prominently displayed in bright red and placed directly below their name, just as any proper tagline should be. The problem is, another college in Wyoming uses the exact same four words for their statement of differentiation. This tagline also happens to be used by an attorney in Milwaukee, a career center in Ohio, and a wealth management firm in Scottsdale. I stopped Googling there, but you get the point.

“Imagine More” and “Inspiring People” are other great examples of higher ed taglines that are utterly and completely undifferentiated.

So what’s an effective tagline for higher ed look like? Columbia University’s “In the City of New York” does an excellent job differentiating itself from competitors. How so? For one, Columbia is the only Ivy League university located in NYC — a distinct benefit for prospective students looking for the big city experience. Brown and Princeton can’t offer that. “In the City of New York” also differentiates Columbia University from the other Columbias in Hollywood, Salt Lake City, and Chicago. There is, after all, only one Columbia in the city of New York.

Remember, taglines don’t need to be provocative to be effective. Columbia’s tagline works because it’s functional. It’s not clever, but it’s crystal clear.

For any communication marketing to work, the words you choose must personally be meaningful to the individual you’re trying to reach. Otherwise, what you’re saying won’t be heard, won’t be remembered, and won’t be acted upon. Meaningful messaging, when done right, will cement the bond between your program and your people. And when enough people embrace your message it can suddenly take on a life of its own.

The University of Kentucky’s “See Blue.” campaign is the perfect case study for a meaningful and memorable slogan that continues to pay off nine years after its debut. Yes, it’s won regional and national awards, but that’s not what makes it great. We know “See Blue.” is working for UK because people love it. And people love it because it’s meaningful to them. They own it. In fact, the UK community chose the slogan after being presented with options by the university’s marketing department. (This, following a long period of research into what students, staff, alumni, and other supporters value, and why UK is special to them.)

“The campus has bought into it. “See Blue.” has taken on a life of its own. I think it may be something that’s here with us forever.” — Kelly Bozeman, Director of Marketing at the University of Kentucky, in an interview with WUKY Radio.

And then there’s the University of Oregon’s “If” campaign. What initially was pegged for a $20 million branding spend, the school’s leadership recently pulled the plug after burning the first $5 million on some highly-polished marketing collateral and this video. What went wrong? The university-wide community never got on board. Unlike at UK, the University of Oregon’s people weren’t invested and they didn’t have a sense of ownership over the message. The work was beautiful, but it wasn’t meaningful.

Developing meaningful, differentiated messaging is a team sport. It’s critical that you get early buy-in from your school’s leadership — especially your president or chancellor — as well as from staff, students, alumni, and the university community at large. Test your messaging, float ideas for feedback, and involve the people who care the most about your brand.

And while there’s certainly wisdom in investing appropriate resources to spread your message around, when you start to see students printing the words on their graduation caps you know you’ve got yourself a winner.

This article is also published on Medium.

Universities coast-to-coast are offering an ever-increasing number of degrees and certificates online these days (craft brewing or turf grass management, anyone?) While the stigma of earning a degree online is not what it used to be even five years ago, there are common obstacles to overcome when it comes to branding and marketing any online program. After all, when deciding which schools to apply for, prospective students will always ask themselves the same questions.

Is this program a good value? How will it look on my resumé?

And, when choosing between on-campus and online options: Is this really the same degree? Really??

With this in mind, I believe many universities are making costly mistakes with how they’re positioning their online vs. brick-and-mortar 4-year degree programs. (I use the term positioning here to describe all the ways a university brands and markets itself in an effort to pull students away from competitors.) Correcting these mistakes may not be easy given the siloed nature of many colleges and universities, but doing so will undoubtedly lead to increased enrollment in online programs.

Below are three case studies highlighting examples of what should and shouldn’t be done with online degree positioning. Whether it’s developing a separate website or a clever new name, maintaining two brands for the same diploma ultimately places doubt in the prospective student’s mind and makes marketing more difficult. There is a better way.

Today, when pursuing an online degree in early childhood development at the University of Washington (UW), prospective students are directed away from the university’s main website to an “Online Early Childhood and Family Studies” website which, confusingly, has a completely different look-and-feel and admissions process from UW’s College of Education.

Above: UW’s College of Education website for Early Childhood & Family Studies — on-campus admissions.

Above: UW’s College of Education website for Early Childhood & Family Studies — online admissions (ironically, it’s not optimized for mobile devices).

A better experience would be to direct students to a shared enrollment page offering two options:

Then, based on how this question is answered, the website would present the various program offerings that match, followed by clear, step-by-step instructions on how to enroll — regardless of whether the student will be taking courses in-person or online.

Using a single enrollment path will allow online learning to be viewed on par with the traditional brick-and-mortar classroom experience, while at the same time leveraging the positive reputation of the university. The goal should be to communicate one university and one high quality education, with the flexibility of two enrollment options.

Another positioning mistake UW makes is how it prices its online programs. In March 2013, the university announced it was offering a new “low-cost online-only degree” in Early Childhood and Family Studies. They touted the online program as an affordable alternative to “help fill a national growing demand for preschool teachers.” But while positioning the online degree as low-cost may sound like a benefit to students, the flipside is that it reinforces the stigma that online degrees are less valuable than those earned in traditional classroom environments. Here’s how costs vary for full-time students, per quarter, for the same degree at UW:

If the University of Washington’s leadership is legitimately concerned about lowering the enrollment barrier for future preschool teachers, a better approach would be to price its online and resident programs the same, say at $3,271 (taking an average of the current pricing for residents and online). This would allow more students to enroll in either option without diminishing the value of an online education.

Some colleges and universities go a step further by pricing their online programs higher than those for on-campus state residents, effectively valuing their online programs somewhere in between resident and nonresident offerings. For example, Oregon State University (OSU) — a top-10 ranked university for online bachelor’s degrees — charges twenty percent more for full-time enrollment in their online program. Here’s how OSU prices its degree offerings, per quarter:

This pricing strategy makes sense because many students applying for online programs are from out-of-state and would otherwise be paying significantly more for what should be the same degree. (OSU does a nice job providing students with a comparison chart of tuition and fees for on-campus vs. online.) Couple this with savings on relocation costs and the ability to fit classes around a student’s work and/or family commitments, paying twenty or even thirty percent more for an online degree is still a bargain. Most importantly, OSU is communicating a critical message of branding singularity: same degree, same university.

On the other hand, tuition prices for online degrees offered by the University of Washington may cause prospective students to wonder, Is this really the same degree?

The University of Southern California (USC), founded in 1880, is world-renowned for its academic and athletic programs. In fact, Times Higher Education ranks USC as having the 13th best reputation on the planet.

However, when the university rolled out its new online program in May 2011, they made a significant mistake by branding it as something unique and different. Introduced as “USC Now”, the university wrote in a press release at that time how the launch of the online program included “a new website — USCNow.usc.edu — to help distinguish USC’s brick-and-mortar offerings from its growing number of online master’s degree programs.”

Distinguish from? Why would a university with a world-class reputation and 130+ years of brand equity want to position its online student experience as anything other than a “real” USC education?

Just a few months after the rollout of USC Now, a new logo and identity system for the university was also introduced. And yet, while the rest of the university was updating logos and signage and websites, the USC marketing department didn’t bother to integrate its online program into the new university branding system for two more years, further widening the perceived gap from “traditional” USC.

After another year passed, school officials finally recognized that the USC Now sub-brand was counterproductive and decided to drop the name altogether, replacing it with the more descriptive “USC Online” in 2014. Today, while the naming and look-and-feel has come together under a single university-wide identity, USC regrettably directs students into a separate website and enrollment path for its online degrees — the same dual-path enrollment experience that UW uses.

Take a look at the website screenshots below to follow the changes in how USC has improved its online degree positioning over the past five years. (Hat tip to archive.org.)

August, 2011: The “USC Now” sub-brand is introduced

April, 2012: A new USC logo is introduced, but “USC Now” continues to use the university’s old branding

May, 2013: “USC Now” is restyled to match the university’s new branding

July, 2014 — present: “USC Now” is changed to “USC Online”

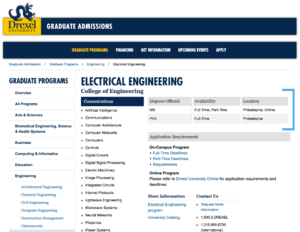

In many ways Drexel University is doing it right. If a student visits Drexel’s website looking for information about a graduate degree in Electrical Engineering, for example, she can quickly see there are two options: either take classes online, or take classes at their Philadelphia campus. Drexel lists them both side-by-side, effectively communicating that the student will receive an identical degree regardless of location.

While Drexel does maintain a separate website for marketing its online programs, students who start at the main Drexel.edu website are presented with clear options for enrollment at the program level. In other words, when students land at the graduate studies page for engineering they have information about every degree option available to them — including those offered online.

Above: Drexel’s College of Engineering website lists on-campus and online programs side-by-side at the program level.

Seems obvious, right? But with so many universities building walls between their online and on-campus degrees, Drexel doing the “obvious” is quite refreshing. It’s a better experience for students, and it’s better serving the university’s brand.

One more thing Drexel does right is tuition pricing. Students pursuing an MS in Electrical Engineering will pay $1,157 per credit, regardless of whether they’re taking classes online or on campus. Same school, same cost, same diploma.

With what we’ve learned from these three case studies in mind, here are a few pointers for improving the positioning of your university’s online program.

Do the positioning challenges described here ring true for your college or university’s online degree program? What else could be done to improve the experience for students and increase enrollment at your school? Let’s talk.

This article is also published on Medium.

If you’re a project manager looking for guidance on finding the best creative partner, or a procurement specialist looking for ways to streamline your company’s policies, this book will help you navigate your search and get results that provide the return on investment you need.

Love ’em or hate ’em, Request for Proposals (RFPs) are standard practice for many non-profit, higher education, and government organizations, and this leaves project managers with few options when they’re purchasing tangible goods or professional services.

If this is your first project lead, make sure you know your organization’s regulations and purchasing limits. Be aware of all your options. With professional services like design and website development, there are lots of reason to avoid an RFP.

But if an RFP is your only option, there is a right way to conduct the process.

Here’s how to develop an efficient RFP for professional services that gets you better results in less time.

1. Establish an effective team who can get on the same page about the project goals. Honest feedback and effective collaboration is an essential part of working with a team. Differences of opinion can be helpful for honing in on the goals and needs of your project. But you must manage the fine line between constructive discussion and derailing disagreement. Don’t be afraid to trim the fat from your team if you have a team member who disrupts the flow of the process.

2. Provide context for the project. Once your team is established, you need to determine the key elements of your RFP. These are important to the responding firm’s ability to develop an effective proposal that meets your organization where you are and solves your problems. These items include:

3. Determine your budget. Some people believe that keeping your project budget a secret from potential respondents helps you to get the best deal.What it really does is hamper your ability to find the partner who is the best fit for your organization. If you hide your budget you will inevitably get responses with a wide variance in cost, experience, and ability. This means more time on your part to evaluate proposals that you’ll never select because of the cost or lack of fit. You will also have wasted money on the part of the firms developing those proposals just for you to throw them out without real consideration.

Clearly defining a budget or at least a budget range allows firms to decide if they can provide you with an effective solution to your problem within the given budget. Those that can will write proposals, and those that can’t will self-select out which saves both parties time and energy.

After setting your budget, instead of focusing on getting the best deal (i.e. price), focus on getting the best value. In other words, focus on identifying the firm who is giving you the most return on your investment given the budget limitations by evaluating the combination of deliverables and quality of work they are offering to complete for you.

If you truly have an open-ended budget for your project, then your team should determine the value of this project to your organization.

These are just a few examples, but all of these questions will help you to determine value and establish a budget. That budget will help all potential partners determine if they are really the right fit for you.

4. Determine respondent requirements. Once you’ve clearly articulated your pieces of the RFP that help to educate the respondents about your organization and the particular project, it’s now your turn to get specific with a few requirements for the responding firms that define how much control your team wants over the creative process, and what you need to see from them to determine best fit.

Be clear about what you want from them, but be respectful of their time. We all know the old adage that “time is money” and RFP responses cost time to develop and evaluate. To be efficient, your goal should be to develop an RFP that is as efficient as possible while still sharing all the information a firm needs to respond. Requirements you should request include:

Of all of these, the most important piece to consider here is whether your team will outline the statement of work (i.e. the solution to your problem), the process, and the timeline for the project, or whether you will simply identify the problem and let your applicants outline these other elements (the process, timeline, and ultimate deliverables) for you.

The benefit of the first option is that your team has control of how you want the work done, and the deliverables you receive at the end of the process. The negative is that when we identify our own problems and solutions we often bring preconceptions to the process that blind us to alternative solutions that may better serve us. This is magnified when dealing with technology because innovation is constantly happening, so you may not even be aware of other solutions that are available to you.

In “Expository Sketch is the New RFP,” Stanford University Technology Strategist Zach Chandler provides good insight as to why engaging your partner firm in helping to solve your problem is essential to successful projects.

While Chandler advocates for doing this outside of the RFP process, if you must seek this problem-solving expertise within the RFP framework, the firm’s response will also give you insight into their process, creative vision, and strategic thinking abilities.

5. Gather any additional information needed. Depending on your project you may consider asking a few additional questions beyond those outlined above. But don’t ask for frivolous requirements, documentation or intrusive information that has no real bearing on your project.

Examples of these frivolous requirements and questions that the MAC team has seen in RFPs include (but are not limited to):

‣ Tell us about a challenge that you’ve faced and overcome.

‣ What project would you like to re-do?

‣ What’s one question we should be asking and haven’t?

‣ After providing a fixed cost bid and an estimate of hours needed to complete the project, please provide a breakdown of each individual team members estimated hours and hourly rate.

‣ Please provide project budgets and scope for similar projects you’ve completed for other clients.

Some of these questions are a waste of time for firms to respond to and your team to read the answers to. This only serves to distract from the only elements of the RFP that truly matter: the quality of the work, the process, the timeline, and the total proposed cost.

As for budgets, the only thing that should really matter is whether you think the work being done for you is worth the price the firm has placed on it. As with all businesses, as a firm does good work and grows, inevitably so will their internal overhead costs. It’s unfair to the firm for your team to try to nickel-and-dime them for the same rate they charged a client five years before. If your team feels the quality of work being proposed is worth the price tag being attached, then the creative firm should have the freedom to distribute the funds how they see fit.

Once you’ve written the RFP and have a solid foundational idea of what you are looking for, it’s time to reach out to potential partners and solicit responses.

Some organizations require you to post an RFP publicly, but many allow you to distribute your RFP selectively to pre-qualified firms. While selective distribution requires some upfront research on your part to identify prospective partners that fit your project requirements, it also provides you with tighter control of the process, shortens the required evaluation process, and eliminates wasted time developing proposals from firms that you’d never actually consider to complete the work.

If you’ve failed to scope the project correctly, or underestimated the project budget given the type of firm you’d like to work with, selectively soliciting bids will also help to identify these issues because your prospective partners will politely decline the invitation to respond.

If you can selectively distribute the RFP, your distribution list may include as few as 2–3 firms or as many as 20 depending on your objectives. The general rule is that if you don’t consider the firm a serious contender, don’t send them the RFP.

Depending on your organization, there may be ways in which your communication is legally limited after the RFP has been distributed. At the very least, you should conduct a pre-proposal conference call where firms can ask you clarifying questions to make sure their proposals are on point.

If you’ve limited the pool through selective distribution and you’re legally allowed to, consider answering individual emails and phone calls. This will allow you to quickly and effectively answer questions, establish a relationship with potential partners, and get insight into their process and attention to detail.

If you’ve done a good job outlining the RFP and soliciting proposals from prequalified firms, the evaluation process should be simple and efficient because you’ll already have a narrow, focused field of responding firms and a clear guideline for how you want to evaluate the proposals.

When you’re writing your RFP and establishing timelines, your team should also internally pre-schedule proposal evaluation meetings as part of this timeline. The last thing you want to do is receive proposal submissions and then spend two weeks trying to nail down your team’s schedule to meet.

Additionally, make sure you’ve established a clear scoring system that is being shared with the respondents as part of the RFP. For example, if your rubric uses a 100-point valuation process and 25 points can be awarded for price, then make sure it is clear what price (or range) will earn the proposal the full 25 points and what will just earn it 15 (or zero) points. A vague scoring system makes it harder for your team to objectively evaluate proposals, and it makes it more difficult for firms to see what you really value in their response.

An odd-number of selection committee members is also best in evaluation in the event that the decision comes down to a majority vote. If you have an even number of committee members or a voting system that requires unanimous approval, make sure you have a predetermined tie-break procedure in place.

If you opted to distribute to a small field (3–5 firms) of prequalified firms, you may also consider if it is possible to have the firms present their proposals to you rather than your team just reading them. This will allow you to ask follow-up questions and clarify aspects of the proposal if needed.

Finally, If you ask for references, use them. References can be extremely helpful in evaluating a firm’s expertise and ability to form positive working relationships if these are key evaluation metrics for your team. If you have no intention of contacting the references, though, then asking for previous work samples will go just as far in showing prior work experience.

Ultimately you can only award your project to one firm, and someone will inevitably be disappointed given the amount of work responding to an RFP requires. However, the firm you select will be your partner for months, if not years. Make sure you treat this relationship with care by responding to emails and phone calls in a timely manner and keeping them up-to-date as you go through the evaluation process.

When you’ve come to a decision, let all responding firms know of your choice and why you went that direction. While you may pass on a firm’s proposal this time, they could be a great partner for you on a project down the road, and letting them know where they fell short will help them to improve for the next project they take on.

While sometimes necessary, RFPs are time consuming for organizations on both sides of the table. Following a simple, clearly defined process and avoiding anything that’s not essential to the process will help you to streamline your efforts and make it as painless as possible for all involved.

This article is also published on Medium.

The Request for Proposal (RFP) process was developed for the well-intentioned purposes of leveling the playing field, minimizing bias, and guaranteeing competitive pricing. It is also the default procurement method for many higher education and nonprofit organizations. When done by the book it holds everyone to the same requirements and theoretically allows the organization to compare like-for-like.

But creative services, or any professional services (lawyers, architects, accountants, etc.) for that matter, aren’t like physical commodities. They can’t be compared like-for-like because while they may be similar, they are inherently different.

Information gathering and comparison is important in your selection of a partner for your next creative project, but doing so through an RFP is highly inefficient and won’t produce the best results or the least costly solution.

Here’s why.

There was a time before the internet when information was more difficult to find, and it’s possible to argue that RFPs were the quickest way to collect the needed information to effectively evaluate creative partners.

But we live in an age where you have endless information at your fingertips. It takes far less time to do a little research on Google than to develop an RFP, send out that RFP, wait for responses, evaluate 20 different 50-page proposals, narrow that down to 3 finalists… then listen to 3 presentations from those finalists, select a winner, then wait 2 more weeks for your procurement office to get through the contract paperwork.

The RFP process is the epitome of inefficiency. If you’re looking to work efficiently and save your team time then avoid the headache of the RFP.

On top of the money your organization loses through wasted time in the RFP process, there are also unrecognized costs of doing business this way.

RFP responses, which can top out at well over 50 pages for creative services when including previous work samples or spec work, take a lot of time to put together. While you’d be hard pressed to find a firm to admit it, there are situations when more time is spent on developing the RFP response then will actually be spent on your project. If you ask for spec work as opposed to previous work samples, then this is definitely the case since asking for spec work is literally asking the responding firms to start working on your project for free before you’ve even awarded the contract.

Creative service firms that consistently obtain business through the RFP process have to make up the money they spend writing your proposal, so these additional costs inevitably get built into the cost of your project.

The bigger problem for you is that even firms who are really good at navigating the RFP process only land a small percentage of the jobs they write proposals for. This means that you aren’t just paying a premium for the extra time spent on your project, but also the time spent developing proposals for projects your selected firm didn’t win.

Business consultant, author, and university lecturer Cal Harrison estimates that the Canadian economy alone wastes $5 billion dollars a year due to this RFP inefficiency. Watch his 3:30 minute video and see the math.

As Harrison said in this TedEx Talk, “As soon as you realize that your inefficient buying process is costing you money, then maybe there is incentive to change. The buyer benefits the most if we change this.”

Additionally, if you happen to get a response to your RFP with a lower than average estimated budget it shouldn’t be viewed as a cost-saving opportunity. Rather, it should be a red flag to you that the firm is:

In any case, none of these scenarios are good if you are looking for the best final product.

When your organizational team sits down to develop an RFP, you are required by the very nature of the document to lay out the project scope and specifications, timeline, (hopefully) budget, and even set guidelines for the environment in which you want the project completed. If this project is for, say, a website redesign, by defining all these parameters you are essentially saying, “We are looking to hire a firm full of creative and qualified people to develop this thing for us, but we already know the solution to our problem and only need your skills — not your creativity — to implement it.”

By doing this you are not just limiting the creativity of the team you are hiring, you are also limiting the potential of the project itself, and therefore the value you get out of your investment. As Stanford University Technology Strategist Zach Chandler puts it:

“But what if our assumptions (laid out in the RFP) are not completely valid? What if we can’t see around all the corners, or see new possibilities of connecting with new methodologies or technologies? A pre-emptive spec locks you into your current best guess … and the web changes faster than that… By being open to the ideas of others, and stating the problem you want to solve rather than telling the vendor how to solve it for you, you may find that the outcome can be far better than you imagined.”

If you are required to use a formal bid process like Chandler is at Stanford University, then his Expository Sketch approach is a great alternative to an RFP. If you have more flexibility in how you approach creative partners, you may consider an initial Discovery Phase engagement with the partner of your choice to access your chosen partner’s entire creative and strategic capability while establishing the project scope and specifications.

They might not say it to your face, but this is how many great creative services firms feel. And it keeps many of them from seriously considering or responding to your RFP.

Don’t take my word for it. This feeling prompted an advertising agency CEO to write this piece for Advertising Age. It led to this panel discussion at SXSW. And it frustrated a very talented designer and illustrator so much that he penned this comic.

The inherent risk and cost of responding to an RFP a firm probably won’t win coupled with the annoyance of wasting time answering questions that are irrelevant to your project (proof of insurance! Company history? Financial record of past projects!!!) just to meet RFP requirements leaves many creative services firms feeling that responding to RFPs is more of a hassle than it’s worth.

This is a problem for you because if you are conducting a truly open RFP process, then this just eliminated some of the very best potential partners for you, and left you with the firms that are desperate enough for the business (and possibly for good reason) to put up with the frivolousness of the RFP.

Creative people love to have real conversations about solving problems that engage their creativity. I don’t know a single creative director or web developer who wouldn’t give you an hour of their time to talk about a project you wanted to work on with their team. In fact, many totally geek out with excitement at the opportunity to do just that.

Do yourself a favor and engage in these real conversations with qualified creative firms that you’ve pre-screened rather than wasting your time and money engaging in an inefficient RFP process that will only stifle your ability to get the best results from the creative process.

This article is also published on Medium.

Request for Proposal (RFP) is a time-tested procurement process that’s consistently worked well for some organizations in purchasing commodities and goods. But in the digital era, using RFPs in the procurement of creative services is an antiquated process that can cost you valuable time and may not lead to the best results.

Think about it this way: an RFP makes sense if your organization is trying to find the best deal on 50 tons of concrete. But if you’re looking for someone to shape that concrete into a work of art, do you really want to start with a process designed to keep all qualified artists at arms length?

Eliminating RFPs from your procurement process for creative and website development services will get you better results and save you the investment of significant time and money.

At this point you may be pointing out the fact that whether you like it or not, your organization has procurement regulations that force you to go to an RFP if the proposed project exceeds a certain dollar figure.

If this is the case let’s frame the problem it in a different way: All projects are made up of phases, which inherently make up a fraction of the total project cost. In fact, many RFPs ask creative service agencies to outline their process and project phases in the proposal response and estimate the cost of each phase. So if a cost can be assigned to each phase, why not make these phases into separate, smaller projects?

This is the route more and more organizations and agencies are going when they begin to understand the downside of RFPs as they relate to creative services. This is a simplistic breakdown for illustrative purposes, but your $50,000 website project can easily become four or five individual projects that each separately fit within the purchasing limits set by your organization. When combined, these five projects equal one awesome website, and operating this way has allowed you to work with the partner of your choice.

And remember how I said avoiding RFPs could actually save you money? Well here’s how: by avoiding the RPF and working directly with your chosen agency, that agency can better anticipate real costs and problems upfront after taking time to understand the project details with you. Otherwise, they are just making a best guess estimate they are locked into once it’s written in the proposal. Most agencies also put an up-charge on RFP work since they’ll only land about 10% of the RFPs they bid for, and time and money is invested into creating each RFP response proposal.

Every project is a little different, so make sure you are working with an expert firm that can help you navigate this process, lay out clear phase projects, and set achievable timelines and goals.

If you’re now intrigued and want to know more, here is a closer look at how our example $50,000 website project could be divided into smaller, less expensive projects.

Discovery is the research and strategic planning phase that starts any successful project. Sometimes overlooked by less experienced firms, this is often the most vital part of any project where you work with the partner firm to uncover needs, define scope and timeline, and establish measurable goals for the project.

If you’re unfamiliar with discovery — or want to know more about how it can help you — check out this free, 8-page Discovery Guide.

If you are going to invest the time and money into developing an extensive online tool for client, customer, or donor engagement, you really should make sure your message and brand image are on point before implementing these elements into your new website.

Content development can include anything from photography, illustrations, video, or written copy that helps to tell your organization’s story.

This phase includes information architecture, wireframing, and visual design mockups. It may overlap with content development and testing, depending on the schedule and nature of the project.

Developing the website can begin as the design phase approaches completion. A web developer takes the static, designed pages and codes them into a functional website. This phase is typically completed with user testing, bug fixing, and launching the site.

If your organization has even tighter purchasing limits than those described above — or if your project contains more extensive requirements and a more hefty budget — some agencies may even be willing to break the outlined phases into smaller chunks. For example, the development and user testing phase could potentially be broken into two separate phases.

My experience has shown that organizations who go to RFPs do so for one of three specific reasons:

Image Courtesy of Kyla Tom, Madison Ave. Collective

When presented properly, the idea of phased projects appeals to these organizations for the following reasons:

Are you following my logic, but still not convinced that RFPs are a bad business model for contracting creative services? A panel of experts presented on RFPs at SXSW a few years ago and their website, NoRFPs.org contains more useful information.

If you begin to engage expert creative firms outside of the RFP process, it will help save you time and money by avoiding the cumbersome RFP timeline and allowing the creative firm of your choice to hone in on the project details with you. Most importantly, you will see the reward in the quality of work produced for your organization.

Do you have an upcoming project and want to test the waters with this new approach? Do a little research and make a few phone calls to agencies that are doing great work for your competitors or in similar industries to find a creative team that fits your needs.

This article is also published on Medium.